Akula submarine

Technical data

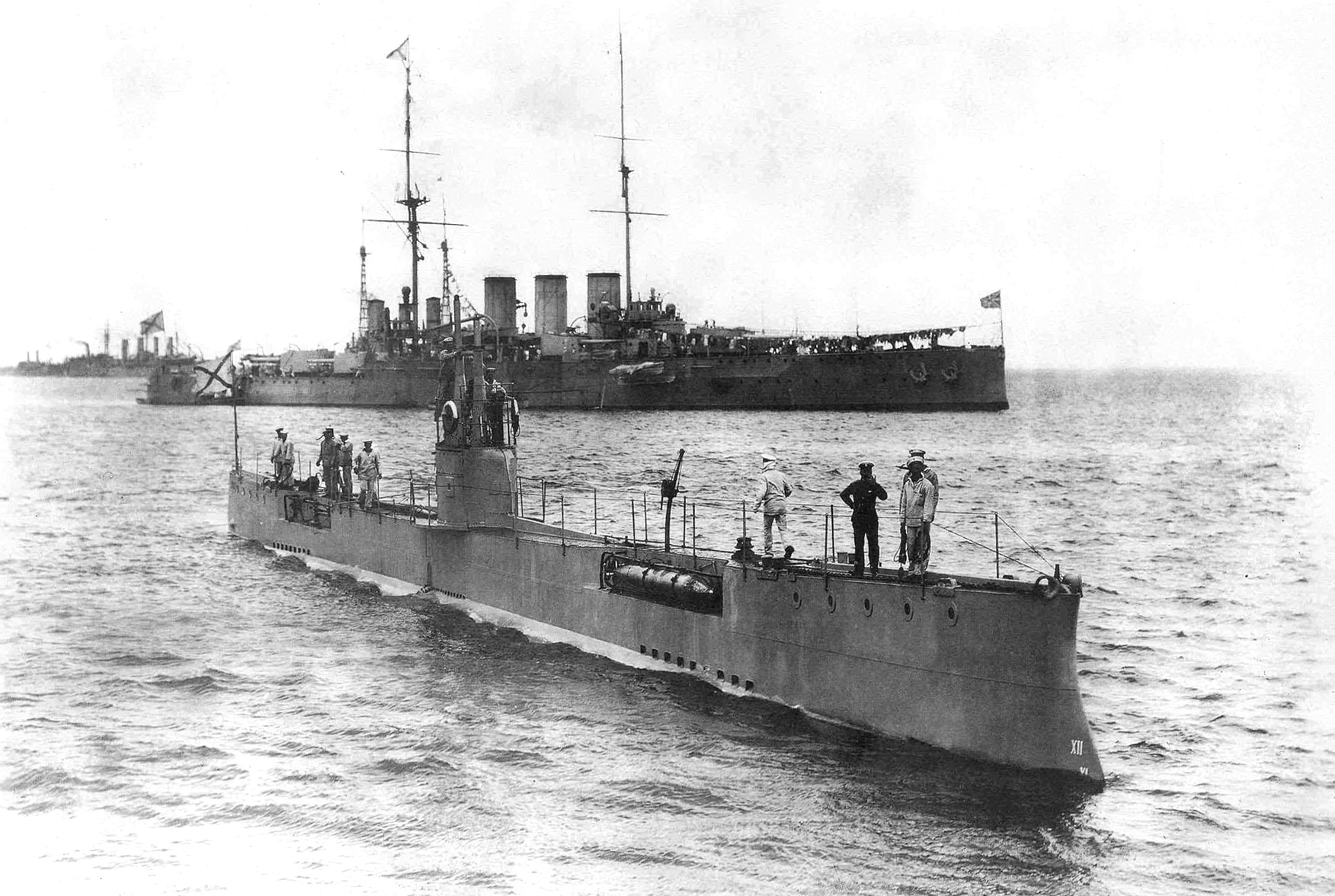

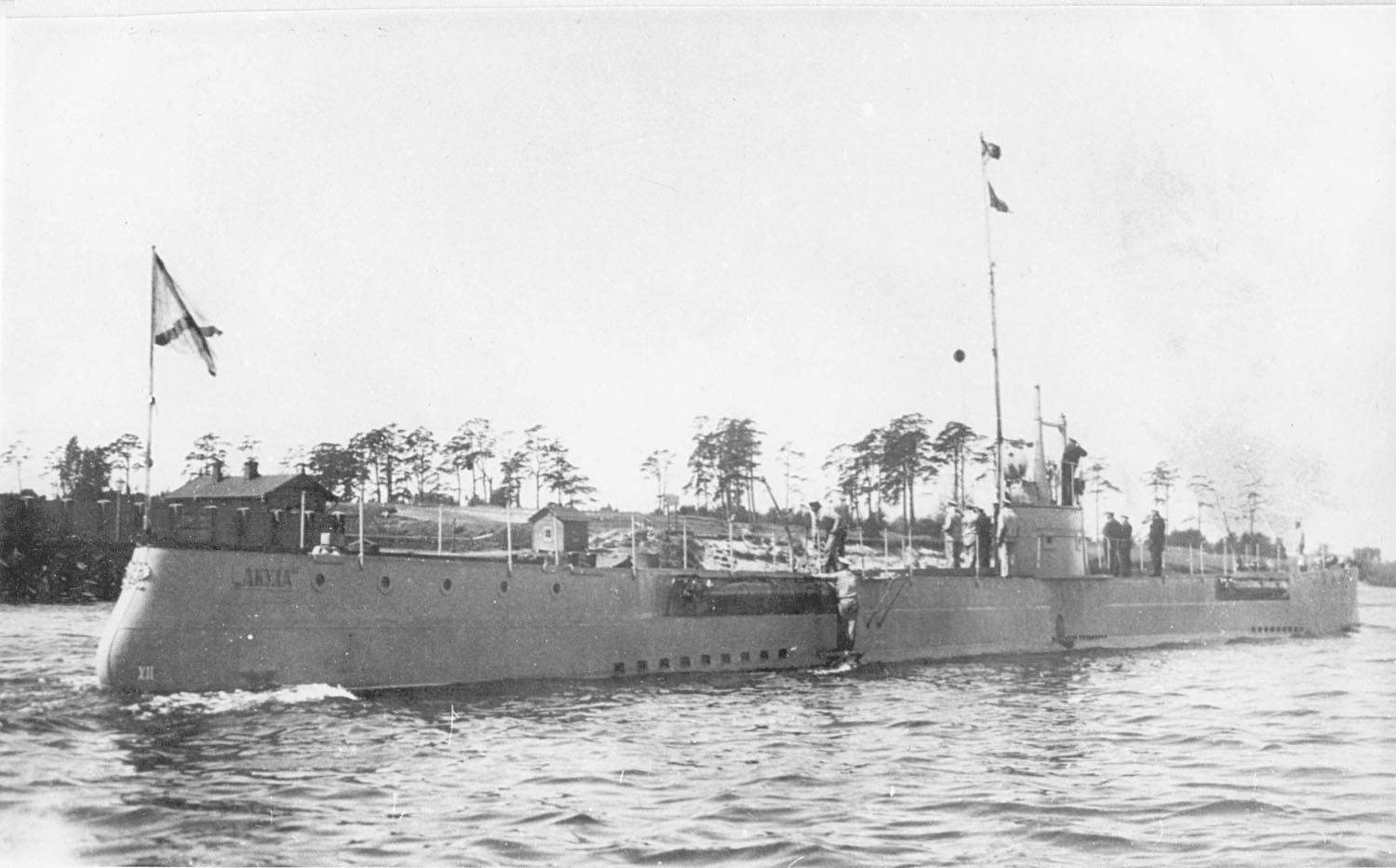

- Displacement: 370 tonnes surfaced, 475 tonnes submerged

- Power plant: 3 x 300 hp (4-cylinder, 4-stroke) Nobel diesel engines, 1 x 300 hp electric motor

- Speed: max 16 knots surfaced, 6.5 knots submerged; economical 9 knots surfaced, 4.75 knots submerged

- Fuel reserves: 15.4 tonnes (diesel), 2 x 63-element, 5,050 Ah storage batteries (3,600 Ah according to some sources)

- Navigation range: surfaced – 1,000 miles at 11.5 knots, 1,900 miles at 9 knots; submerged — 35 miles at 6.5 knots, 90 miles at 4.75 knots

- Armament: 4 x 457 mm torpedo tubes (2 x bow, 2 x stern); 4 x Dzhevestky torpedo launchers; 2 x 7.62 mm machine guns (removable); 1 x 35 cm searchlight; 2 x Hertz periscopes (since 1915: 1 x 47 mm gun; 4 x obstacle mines)

- Radiotelegraph: 1 x 0.5 kW station, 100 mile range

- Crew: 2 officers, 2 warrant officers, 29 enlisted

- Dive time: 3 minutes

- Surplus buoyancy: 25%

- Operating depth: 50 meters

- Sank on 15 November 1915 as a result of a drift mine explosion when surfaced

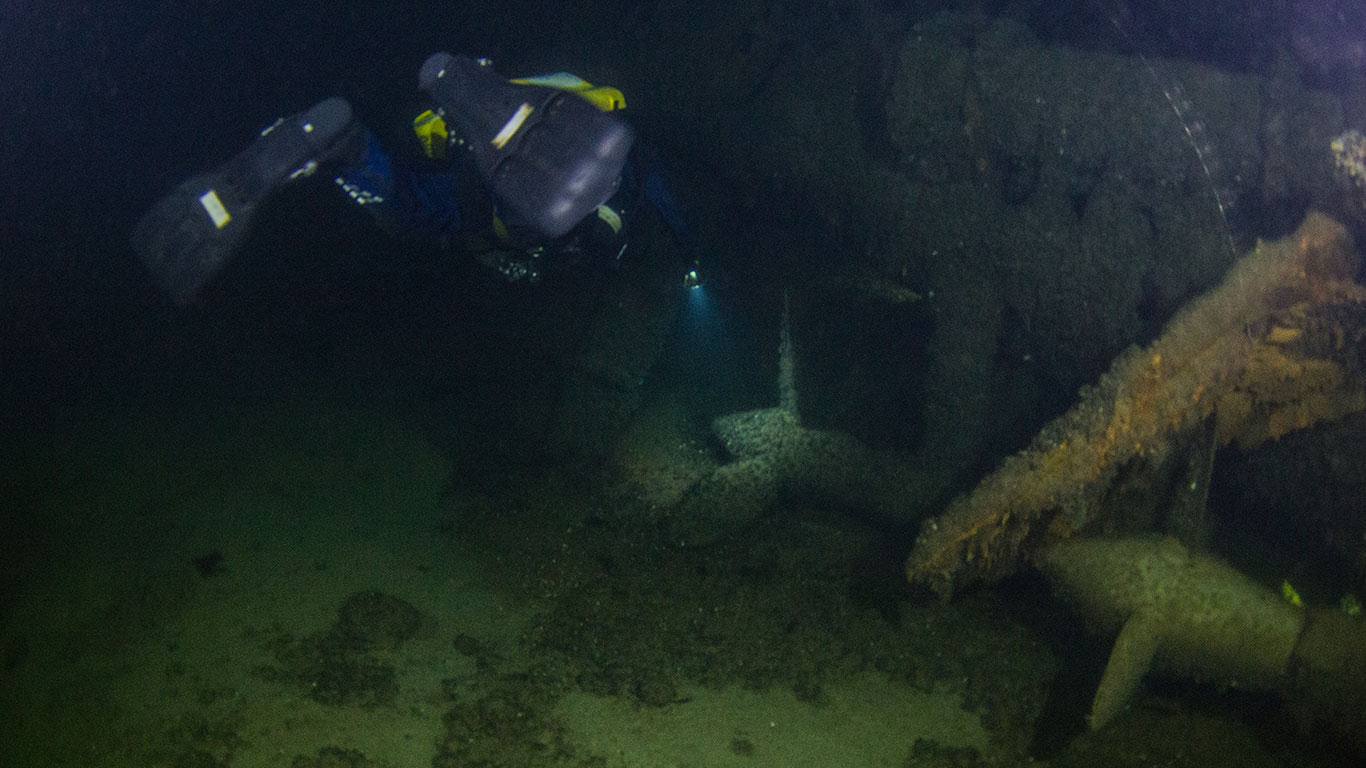

- Found by Estonian diver Tanel Urm in 2014, explored and identified during a joint expedition with our team

- Depth: 35 meters

Submarine history

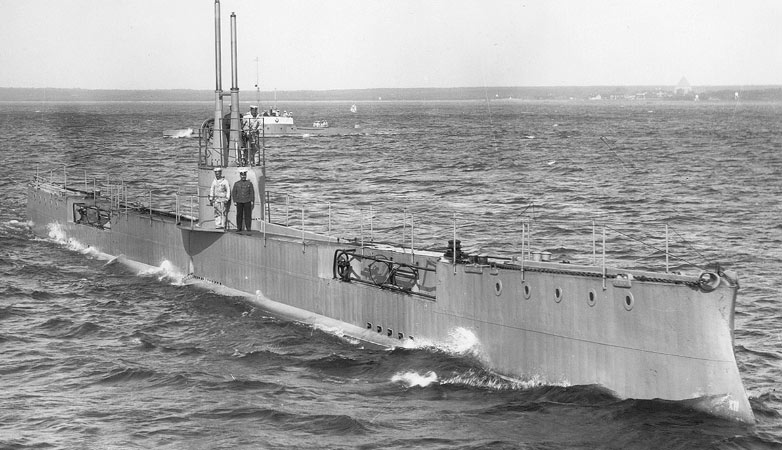

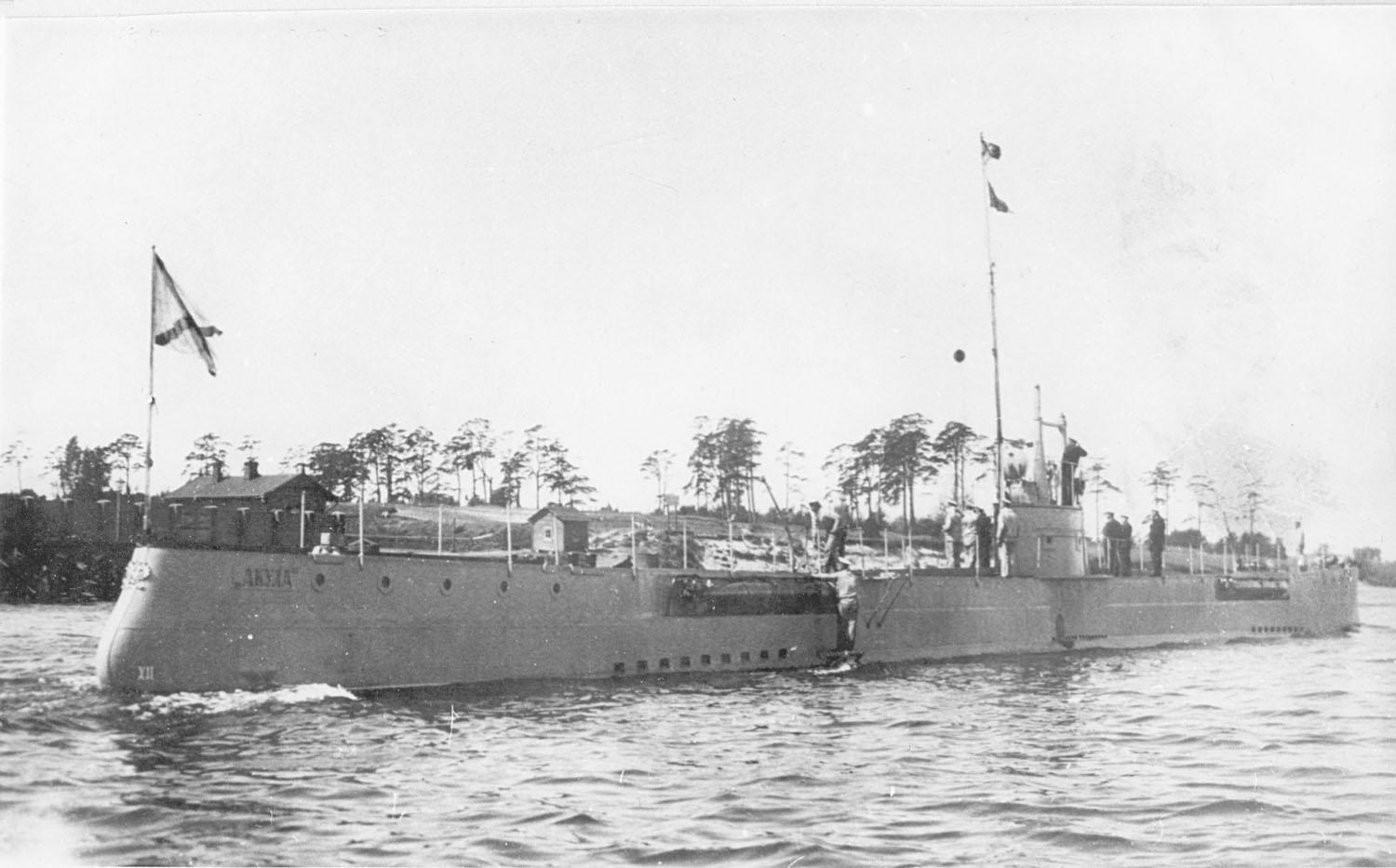

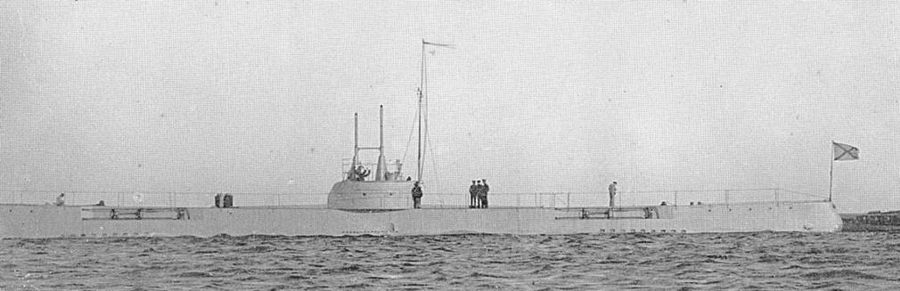

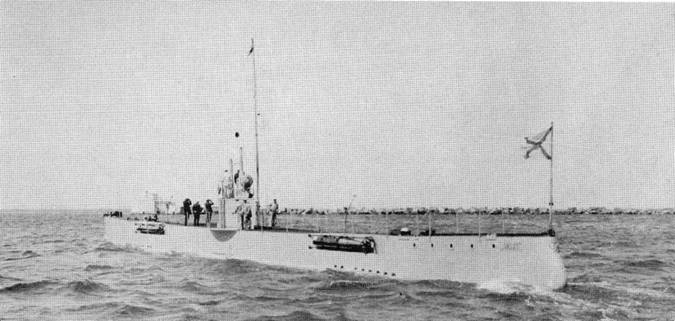

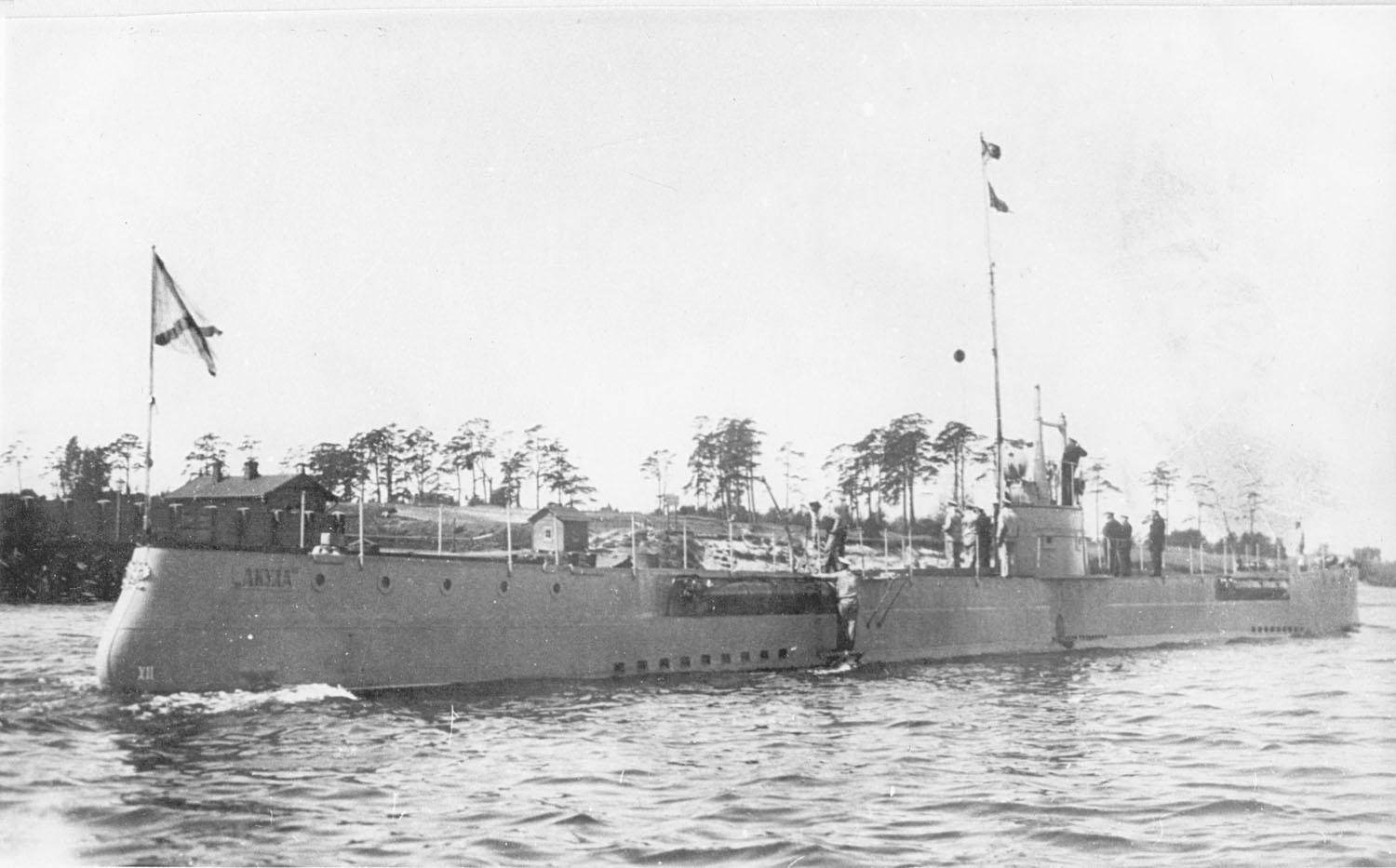

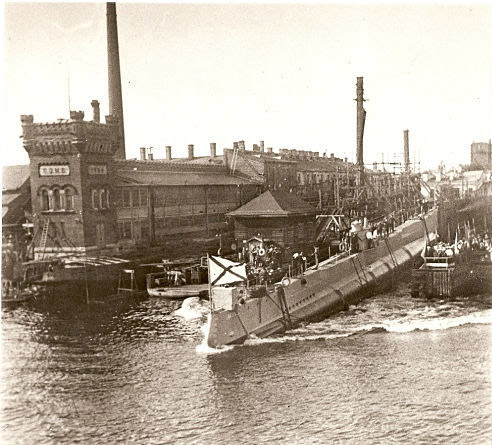

Commissioned on 14 June 1907. Laid down in December 1906 at the Baltic Shipyard in St. Petersburg. Launched on 22 August 1909, entered service on 6 October 1911.

During WWI, she conducted search operations along enemy communication lines, conducted and covered mine-laying operations by the fleet’s light ships; she conducted a total of 17 combat patrols.

On 7 November 1914, she went on a patrol to Dagerort and then, instead of returning, at the commander’s initiative she remained at sea and sailed to the Swedish coast.

This patrol was the first time that the Russian Fleet hunted for the enemy, instead of its usual positioning tactics. Subsequently, hunting tactics would bring the Russian Fleet many successes on both the Baltic Sea and the Black Sea.

On 8 November 1914, she sighted the Amazone cruiser at Gotska Skande and at 4:05 fired one torpedo from a distance of roughly 7 cable lengths at the approaching destroyer. The Germans saw the torpedo’s wake and turned out of its way. This was the Russian submarine’s first attack.

The surface and dive engines were overhauled in the winter of 1914-1915 at the Baltic Shipyard. Additionally, a 47 mm gun was installed, as well as a training and mine-laying device to deploy four obstacle mines.

In November 1915, the sub sank during its 17th combat patrol while laying mines between Libava and Memel. Nothing was known about her fate for 100 years. The most plausible theory was that the mine-laying equipment reduced the submarine’s surface stability and she capsized during a storm.

Commander: Lieutenant N.A. Gudim (1914-1915)

The Akula submarine was one of just a few WWI-era Baltic Fleet submarines that was able to operate in the enemy’s coastal waters. This largely determined her further intensive combat service.

Combat patrol story

On the evening of 4 December 1914, the Akula submarine was in the open sea. A snowstorm was raging, the wind was was whipping the heavy snow – the winter Baltic was storming. At times, the visibility was nearly zero. The submarine’s commander, Captain Second-Class S.N. Vlasyev, watch officer, Midshipman K.F. Terletsky, and helmsman, Petty Officer Ivan Pasteh, were on the bridge. The waves were lashing around the sub, but she continued stubbornly onward, as Vlasyev was searching for enemy ships. Before going to sea, headquarters informed the submarine commander that the German cruiser Augsburg had been spotted: a tempting target. So, the Akula was sailing on the surface, although in such weather she should have submerged long ago.

It seemed nearly impossible to see anything in the whiteout. But no, it was possible! «Ship on the starboard side! Distance 20-25 cable lengths! Moving on a collision course!» Ivan Pasteh, who was one of the best helmsmen in the Baltic Fleet and had only recently had a merit promotion to petty officer, had come through again. «Well done», the commander replied, peering into the distance. «I see it! The Augsburg! All hands below deck!» Terletsky and Pasteh jumped into the hatch. Before following them, Vlasyev brushed the snow off the periscope. However, the blizzard was getting worse with every passing minute. The commander went below and closed the hatch, then leaned against the periscope, but could see nothing at all. The lenses were instantly covered in snow. The sub was blind. Was it possible to attack in such conditions? «Konstantin Filippovich, what shall we do?», the commander asked Terletsky and, without waiting for an answer from the watch officer, said: «There’s only one way out: we need to return to the bridge – decks awash, I’ll command from above. Helmsman remain below. Let’s go!»

The pumps roared to life. The Akula submarine began drawing water into the stern ballast tanks. Bubnov’s first submarines took a very long time to submerge – a full three minutes – so the commander decided to bring the submarine to decks awash position, leaving only the bridge surfaced.

In this case, it takes just one minute to submerge. Even if an enemy cruiser were to spot the submarine, which in these conditions was highly doubtful, it would have time to dive.

Opening the top hatch, Vlasyev and Terletsky returned to their positions on the tiny bridge, the lion’s share of which was occupied by the two periscope shears. Both sky and sea were attacking the officers. Hurricane-force winds were driving the snow, and the waves were furiously lashing the bridge. The bridge flooded both when submerged and with decks awash, when it was nearly level with the surface of the sea, and practically nothing separated the officers from the shock of the waves. It was almost as if they were riding the sub into battle. Even the slightest mistake by the helmsman would send the bow under and wash the officers overboard. Once, that very thing happened on the Peskar submarine. A tugboat stopped (the sub was being towed), the helmsmen miscalculated, and both the commander and mechanic, who were on the bridge, went to a watery grave.

Terletsky and Vlasev remembered that case. However, that was during the July heat, and this was a freezing December blizzard. The two men courageously fought on the Akula’s bridge in the raging sea. This was a fight indeed. And there was a reason… It was as though they were accompanied by Vlasyev’s wife, Joanna Alexandrovna, whom Terletsky devoutly loved. Vlasyev knew this, but felt no enmity toward his subordinate: another woman took Joanna Alexandrovna’s place in his heart. A break-up was inevitable, but Vlasyev was not indifferent about who would raise his children: two sons and a daughter. It had already been decided that the children would stay with their mother. The commander had known Terletsky for years, was sure of him, but couldn’t help but to once more test the mettle of the man whom Vlasyev’s children would call stepfather. So, there was more than just the needs of battle forcing the submarine commander to take the desperate step of «riding» the submarine into combat.

Wave after wave washed over the submarine… Water was streaming into the open hatch. The situation was very bad. The submarine was taking on extra water at a time when the ballast tanks were carefully calculated and balanced. «This is bad», Vlasyev yelled, «We’ll sink the sub. We need to close the hatch!» «But how will we contact the helm?», Terletsky yelled, practically into the commander’s ear, as the sea was simply bellowing. «We’ll send commands through the upper vent valve, since it’s open now. Close the hatch!» Terletsky did as commanded. The German cruiser approached. Its silhouette suddenly appeared as the blizzard made a brief respite, as if exhausting its anger, then disappeared again into a veil of snow. Torpedoes away! However, they missed. In his debriefing, Vlasyev reported: «The likely causes were the following: poor targeting due to low visibility, changing snow conditions, as well as because, having remained topside, we had to be careful not to be washed overboard – when we fired, I was barely managing to hold onto the handrail.»

The report also stated: «I consider it my duty to note the dedicated work of the officers and team members while sailing in such harsh conditions… it is also necessary to note the dedication and contribution of the watch officer, Midshipman Terletsky, an outstanding officer in all respects whose competence, character and knowledge in service merit special distinction.»

Joanna Alexandrovna would soon take the children and leave Vlasyev for Terletsky. Unmarried (until a divorce agreement could be filed), they lived in Revel together. But Terletsky received command of the Okun submarine, which was based on the Aland Islands. Joanna Alexandrovna traveled to the Aland Islands in late November 1916 to visit Terletsky. Their few days together passed quickly. On 1 December, Terletsky took Joanna Alexandrovna to the Shiftet freighter, which was sailing to Revel, and then went to the harbor, as he had a combat patrol coming up.

The morning fog was like a curtain, revealing the pines and granite of the Aland Islands. Terletsky piloted the Okun submarine out of the harbor. The Shiftet was sailing several cable lengths away. Terletsky was watching the steamer through his binoculars. He thought that he could see Joanna Alexandrovna at the stern. After all, she knew that Konstantin Filippovich would follow in the steamer’s wake for a while, until submerging. Suddenly, there was a flash of fire under the stern of the freighter. The blast wave reached the sub and rolled the Okun onto its side. The freighter sank almost immediately, its bow jutting into the air. Then came another dull rumble – the steamer’s boilers exploded in the icy water. Joanna Alexandrovna was not among the few who were rescued.

From the report of the commander of the Fifth Detached Artillery Company of the Abo-Aland position on the Maritime Front:

02.12.1916: «At 09:35, a steamer sailing from Marienhamn was covered in thick smoke, objects were seen flying in all directions. The faint sound of an explosion followed. After around three seconds, only the sinking stern could be seen, and within 10 seconds it had all plunged into the water.»

Excerpt from the Shiftet steamer’s casualty list:

Boatswain’s Mate Sergei Ivanov, helmsman of the Okun submarine, who was escorting the wife of Captain Second-Class Vlasyev.

Private citizens and civilian officials:

[…]

Wife of Captain Second-Class Vlasyev […]

There were 65 names on the list of casualties. Approximately 10 people were rescued, one of whom died on the way to Marienhamn. Thus died Terletsky’s beloved. Two of Vlasyev’s three children (by this time, the oldest son had entered the naval college) remained in the hands of the commander of the Okun submarine , K.F. Terletsky. He was deeply faithful to the memory of Joanna Alexandrovna, and Vlasyev’s children remained under Terletsky’s tutelage a long time. The youngest son – Rostislav – considered him his father for decades, not noticing a difference in his attitude toward him and Boris, Terletsky’s son from his second marriage. Boris Terletsky died bravely in the beginning of WWII, while serving as a lieutenant in the armored corps.

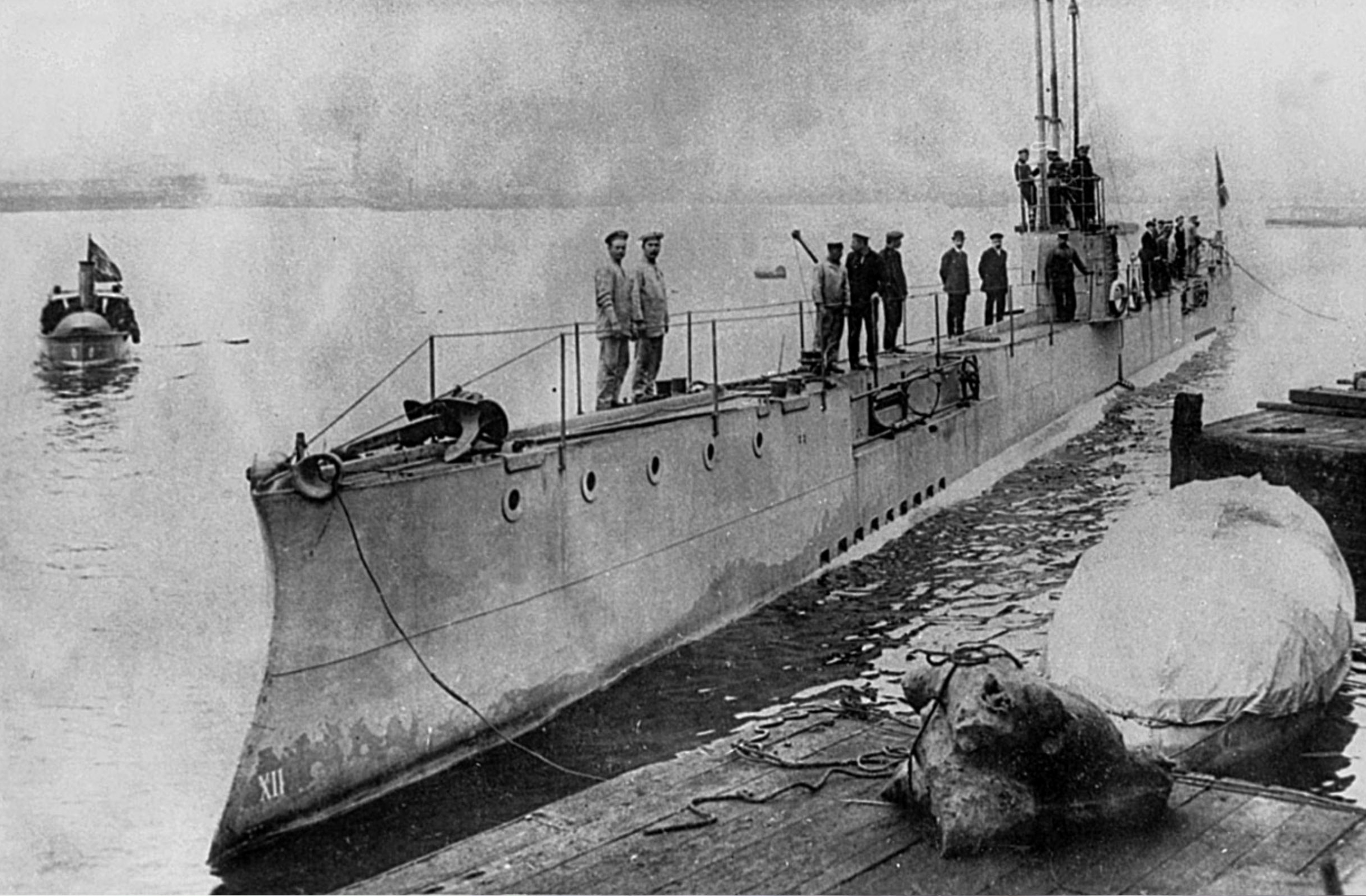

In the winter of 1914-1915, during repairs to the bow, a 47-mm caliber gun was installed. Since the Baltic Fleet had no specialized mine-laying submarines, in the fall of 1915 the Akula was outfitted with a device to transport and deploy four of the mines used on the Baltic Fleet’s Krab underwater minefield.

Hooks fastened the mines in nests behind the conning tower on the upper deck, and after their transport fasteners were released they would be slid overboard by hand along pillar brackets. Practical tests conducted during the Revel raid gave positive results. On 14 November 1915, the submarine’s commander, Captain Second-Class N.A. Gudim, took the Akula on its 17th combat patrol to deploy mines south of Libava.

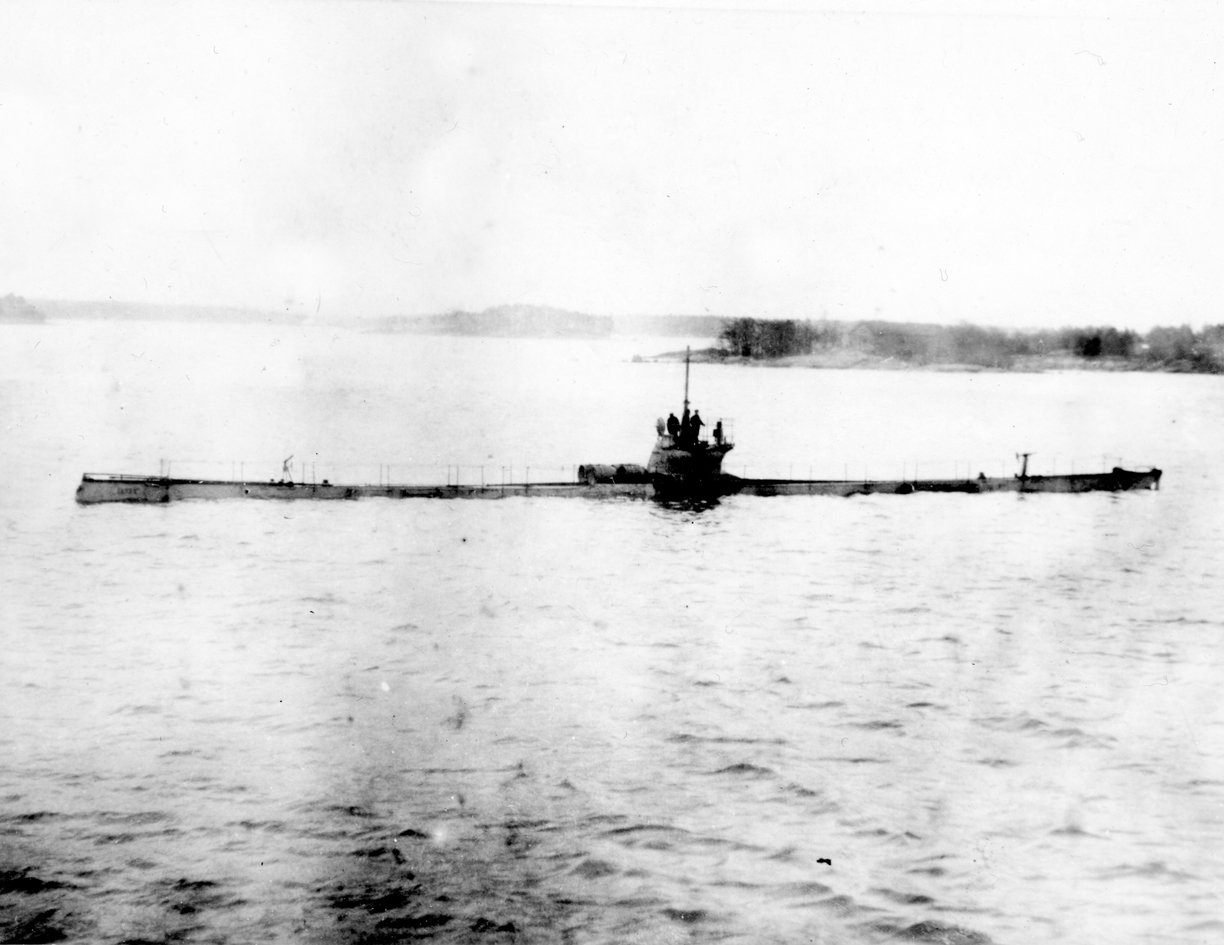

On the evening of 15 November 1915, the Akula submarine was spotted by coastal stations along the shore, where it was riding out a storm. The ship was not seen again – the reason why the Akula submarine sank remains a mystery to this day.

The Akula was the Russian Fleet’s first submarine lost in combat.

Reflections among the Russian submarine community following the Akula’s sinking

Notes of V.A. Merkushov, Okun submarine commander in 1914-1915. Submariner’s notes, 1905-1915. Compiled and edited by V.V. Lobytsyn. — M.: Soglasie, 2004. — 624 pp., ill. — isbn 5–86884–094–1. Press run: 1,000 copies.

13-26 December.

In three days, it will have been a month since the Akula went on its first mine-laying run at Vindava. Too much time has passed, and with pain in my heart I must assume she sank…

This is the first combat loss in the Baltic Fleet’s Submarine Division. If the Germans had sunk the Akula, they would long ago have proclaimed it to the whole world, thus, it seems likely that nobody will ever know how, where and why she sank. Did she hit a mine, get caught up in nets – which the railing for the four obstacle mines near the conning tower would have made particularly easy – or was there some accident during diving: nothing is known.

Perhaps the Akula sank from an explosion of one of its own mines. (Once, at Revel, a mine’s fuse activated during diving and it armed; they managed to disarm it, but this case is very revealing.) Maybe, while under way, due to the rolling and waves striking the Akula’s hull and the unprotected obstacle mines, one of them became armed, struck some object floating on the surface, and detonated…

Or perhaps one of the mines’ mounts was unable to withstand the repeated strong impacts of the waves and broke or was weakened; the mine slipped, armed and detonated on the sub’s hull.

It could also be supposed that the submarine simply capsized, although in avoidance of this the Whitehead mines were only used in internal launchers, and the four external Dzhevetsky-Podgorny launchers were not loaded.

Whatever the case, after departing from Revel on the morning of 16 November, a storm forced the Akula to anchor at the Lower Dagerort lighthouse, after which she went to sea and was lost, taking four officers and 28 shipmates with her – old, experienced submariners…

Until the new submarines of the 1912 program entered service (Bars, Gepard and Vepr), the Akula was our best submarine, led by one of our most experienced commanders, Captain Second-Class Nikolai Alexandrovich Gudim. The executive officer was Lieutenant Gersdorf, the helmsman was Lieutenant Kopets, and the watch officer was Midshipman Chistovsky.

Due to the crew’s limited knowledge of the new obstacle mines, the first combat patrol was accompanied by Lieutenant Stefan Kalchev – he was of Bulgarian descent, graduated the naval college with me, joined the Russian Fleet in 1911 and was the assistant of the mines’ inventor, Captain First-Class Shreiber.

This is the same Kalchev who had invented a special drifting mine with near-zero buoyancy, intended specifically for the Bosporus. His intention was for the cylindrical mechanical mine to float freely with the current at a set depth until it ran out of electrical charge, say around a week, but the float time could be shortened to several dozen minutes.

Thrown into the mouth of the Bosporus, the mines would be carried by the current, unnoticed by anyone, deep into the strait, where they would detonate after hitting the submerged part of a ship underway or at anchor, or a net or embankment, sinking the ship, severing the net, or destroying coastal structures.

I don’t know how far the development of these mines had advanced, and who knows whether it will be finished now?

Thanks to its reliability, sailing range and relatively fast dive time, the Akula was constantly sailing to enemy shores, repeatedly attacked German ships, launched mines at them, but despite the commander’s massive energy and the crew’s endurance, they were not successful.

Nonetheless, Nikolai Alexandrovich was, without a doubt, one of our best, most worthy and talented submarine commanders. He happily combined eight years of continuous service in the submarine fleet with the inclinations and ability to apply theoretical insights to tactical problems.

Under a different command at the Baltic Fleet’s Submarine Division, Captain Second-Class Gudim would most likely have been transferred to the Naval General Staff, where his experience, knowledge and inclinations could have fully manifested themselves.

With his death, we have lost an officer who could have created new submarine tactics that do not yet exist in any of the world’s fleets, due to how recently we have begun sailing underwater…

On the evening of 15 November 1915, the Akula submarine was last seen by the Russian observation posts on Ezel Island.

Summary

The Akula was the first truly Russian combat submarine, designed and manufactured at Russian shipyards. She was one of the world’s best pre-war submarines.

She was the first submarine in the Russian Fleet to have diesel motors installed.

At the beginning of WWI (before the Bars-class submarines entered service), the Akula was the Baltic Fleet’s most advanced submarine, completing 16 combat patrols in 16 months, and sinking on its 17th patrol.

She conducted the Russian Fleet’s first submarine-launched combat torpedo attack.

The Akula was the first submarine in the world to fire several torpedoes at once.

In 1915, due to the Baltic Fleet’s acute shortage of ships for concealed mine-laying along enemy coasts, the Akula submarine was equipped with deck gear to transport and launch four anchor mines.

The Akula was the first Russian submarine lost in combat.

Seafloor conditions

The submarine is excellently preserved, laying at an almost even keel on a course toward the proposed mine-laying site. All four mines that she was carrying lie side-by-side: the outer hull has been destroyed over the years and the mines fell down. The main hatch is open, the compass is installed, the periscope is stowed: the submarine sank while surfaced. The brass inscription «Akula» is visible on the remnants of the outer hull.

The bow of the sub has been torn off by an external explosion on the starboard side, and the part of the bow that has been torn off lies 10 meters behind the stern. Most likely, while sailing on the surface, the submarine hit a drift mine (there was a German mine field nearby, where Russian minesweepers were working). The explosion tore off the bow of the ship, which fell vertically to the seafloor, and the rest of the sub sank more gently. The Akula had no isolated compartments, so the submarine most likely sank almost immediately. The entire crew was undoubtedly killed and most of them are likely still inside the shipwreck.